Astronaut diary. Week 6 – The Human Factor and ascents into free space

Monday 2 December

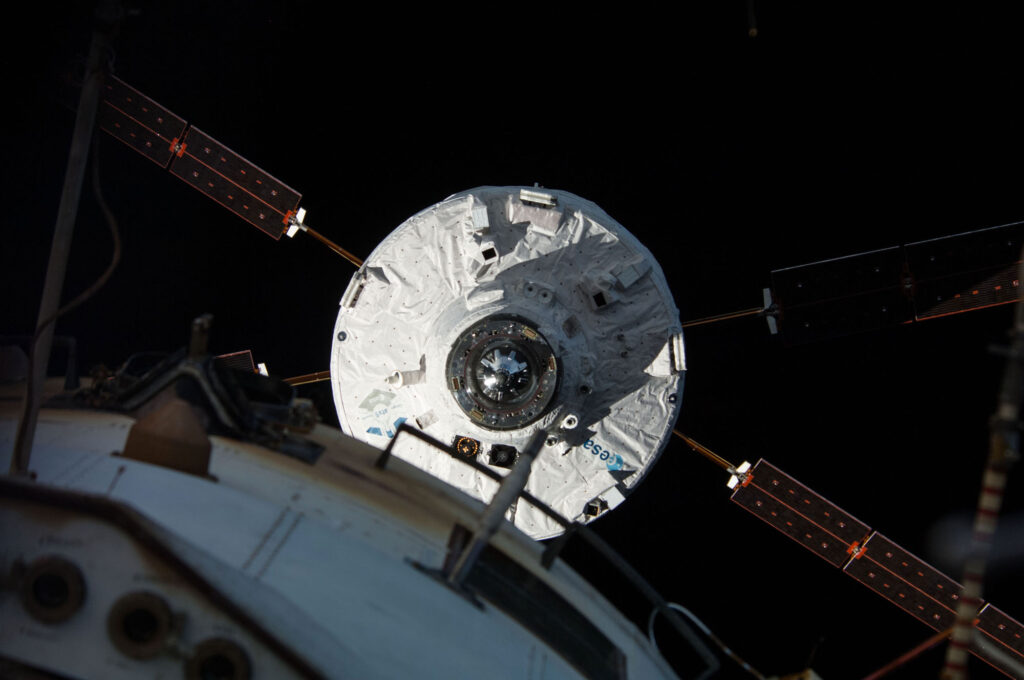

The week just started with training on Visiting Vehicles, both “cargo” and “crewed”. It covered space vehicles both historical and current – i.e. Space Shuttle, Soyuz MS, Crew Dragon and Starliner. Of the cargo ones, Progress, ATV, HTV, Cygnus, Cargo Dragon and the future Dream Chaser. In addition to these, we also discussed the various systems for “docking” and “berthing”, or for docking a vehicle to the ISS, where the docking occurs actively from the side of the spacecraft, and for docking where the vehicle is passive, its docking ends in close formation with the ISS, and the final docking occurs using the ISS robotic arm.

So, in particular, we had the opportunity to learn about the International Docking System (IDS), the Russian RDS, and the Common Berthing Mechanism (CBM). One of the differences between the systems is the size of the ports – while the docking ports are 80 cm in diameter, the berthing ports (i.e., the CBM mechanism) have a square hatch with a side length of 1.3 m. They therefore allow the relocation of bulky payloads, such as individual gulls from the ISS modules. Quite interesting is the fact that the Russian RDS system, in contrast to the international IDS, allows the transfer of fuel and water between the spacecraft and the service module after docking. As far as the cargo carried on the ISS is concerned, it is always limited by the capacity of the spacecraft – both in terms of mass and volume. Interestingly, the volume limit is almost always reached before the mass limit – the average density of cargo is around 200 kg per m3.

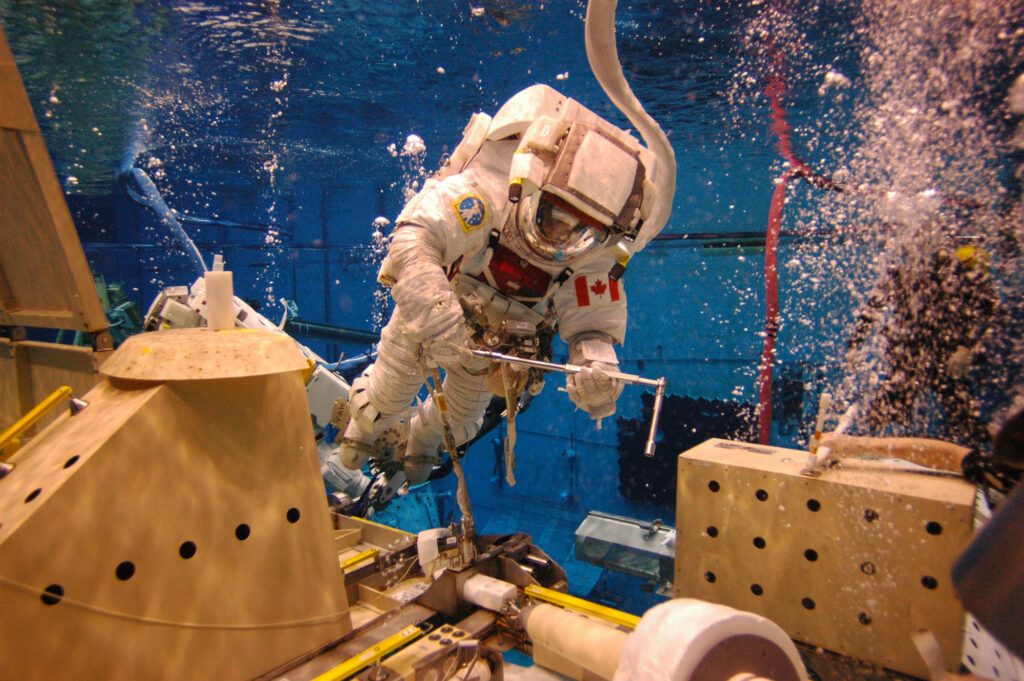

The afternoon continued with a lecture by Hervé Stevenin, EVA instructor, on the EVA training sequence here at the European Astronaut Centre. We discussed the history of ascents into open space, from Alexey Leonov and Ed White, through the Apollo program, to the present day. Almost five hundred spacewalks (468 to be exact) have been made over that time, more than half of which have taken place on the ISS. Most of the talk, however, was devoted to the EVA training scheme here at the Neutral Buoyancy Facility (NBF) and the collaboration with NASA. Also worth mentioning is the testing of technologies for lunar missions at the NBF.

Tuesday, December 3

On Tuesday, we spent almost the entire day dedicated to HBP. We started with lectures on debriefing methods and teamwork, and continued with computer simulation and practical activities, where we could try everything in practice. The most beneficial part of the HBP training was probably the meeting with Luca Anniciello and Luca Parmitano (here online only), who shared with us their perspective on astronaut training and cooperation within individual teams during flight preparation and during the flight itself.

The day was punctuated by another lecture by Hervé Stevenin on the EMU (Extravehicular Mobility Unit) spacesuit. The EMU is an American spacesuit designed for spacewalks. The pressure inside is only 0.3 bar, less than a third of the atmosphere. This is because too much overpressure compared to the surrounding near-vacuum would make it impossible to move in the spacesuit – it would be inflated like a Michelin figure. However, due to the lower pressure, the atmosphere in the spacesuit is made up of 100% oxygen, so that the partial pressure of oxygen is always above the physiological norm, which ensures oxygen exchange in the lungs.

The lecture focused not only on the technical description of the individual parts, i.e. the Space Suit Assembly (SSA), Portable Life Support System (PLSS) and the SAFER (Simplified Aid for EVA Rescue) safety device, but also on how the so-called fitting of the spacesuit to a specific astronaut is carried out – i.e. adjustment so that all parts of the SSA (i.e. parts for legs, hands, gloves, etc.) are the right length. The entire spacesuit, including the SAFER device, weighs about 145 kg.

SAFER is a rather interesting thing. It is a lightweight version of the iconic MMU (Manned Maneuvering Unit) device, which is used to rescue an astronaut in the event that all the safety ropes connecting him to the station are lost during an ascent into open space. SAFER is equipped with 24 nitrogen-fueled cold-gas thrusters that allow for six degrees of freedom of maneuver – rotation and translation in all axes. It is used only in emergencies and is controlled by the HCM (Hand Controller Module).

Part of the lecture was also devoted to injuries that occur during EVA training. Working in an EMU spacesuit is not a very comfortable affair. Each training “run” in a spacesuit in the Houston NBL pool takes a very long time – typically 6 hours. However, you need to add to this the time spent in the spacesuit before and after the dive. This easily adds up to eight hours. Approximately every fourth training dive in an EMU results in an injury – mostly minor hand injuries.

Wednesday, December 4

Wednesday belonged entirely to HBP. First, several lectures on the topic of “feedback”, i.e. how to effectively provide feedback. This was followed by a lecture on “error management”, describing the influence of the human factor and error management in organizations. The vast majority of HBP techniques and methods come from aviation – partly civil, partly military. Concepts such as the “Swiss cheese model”, which is very well known in the field of flight safety, or methods for briefing, debriefing or feedback, are nothing new to professional pilots. For example, processes that are commonly implemented in combat squadrons (i.e. Western ones), and which also work very well in our tactical air force, are a perfect example of how human errors can be used to increase the performance and efficiency of an organization and to increase flight safety. Instead of being the cause of organizational failure, they become one of the sources of success. This is closely related to the corporate culture in the organization, the quality of leadership and the processes set up for voluntary reporting of one’s own mistakes, sharing experiences with others and finding systemic solutions instead of pointing fingers at individuals. Modern fighter squadrons and their “fighter pilot culture” known for their extensive use of debriefings and corporate “no blame” culture, creating an environment of trust for sharing mistakes, are an excellent example of this.

The training was again interspersed with computer simulations and practical exercises. At the end of the day, we had the opportunity to connect remotely with our Swedish colleague Marcus Wandt and listen to his perspective on the matter, what would the most recent European participant in a manned mission to the ISS, specifically his Muninn mission as part of the Ax-3 flight.

Thursday, December 5

Thursday belonged partly to HBP – this time the topic of “self care”, or the management of long-term stress and getting along with other members of the team in times when we or our colleagues are under greater, often personal, stress. The afternoon was then dedicated to training on the European Space Agency’s educational programs and the involvement of astronauts in them. The most interesting was the lecture on the activities of astronauts on the ISS, aimed specifically at students and children. That is, demonstrations of various physical principles in weightlessness, video calls with schools directly from the ISS, or radio connections with amateur radio stations on the ground.

Friday, December 6

The week ended with the last in a series of lectures on EVA. This time, it was about getting acquainted with the course of EVA training in Houston, USA, and the NBL (Neutral Buoyancy Lab) pool there. It is a little deeper and larger than the NBF in Germany – it is 12 m deep and about the size of a hockey rink. In addition to theoretical lectures and getting acquainted with the EMU and technical tools used during EVA, the training in the NBL consists of a total of 9 “runs” in a spacesuit underwater. It usually starts at 6:30 in the morning with the preparation of the spacesuit, briefing and dressing. You go underwater about two and a half hours later. The actual content of the training “run” begins about half an hour after immersion and usually lasts six hours. This is followed by taking off the spacesuit, a shower and about an hour of debriefing. The whole process takes about nine hours without stopping (i.e. without a break for food). Each astronaut can do a maximum of one “run” per week, as this is an extremely physically demanding activity.

At the very end of the day, we had the opportunity to take an excursion to the newly built LUNA facility, which simulates the lunar surface. It now contains a simulant of lunar regolith (dust) and moon rocks. A lighting system will soon be installed, which is supposed to simulate the exact position and intensity of the Sun and Earth’s light, as well as a load-relief system, which will in turn simulate low gravity on the Moon (one sixth of Earth’s). The facility will be used for research, testing, but above all for astronaut training.