Measurement of the human stress level in the climate chamber of the FSI VUT by the reservist astronaut Major Ales Svoboda

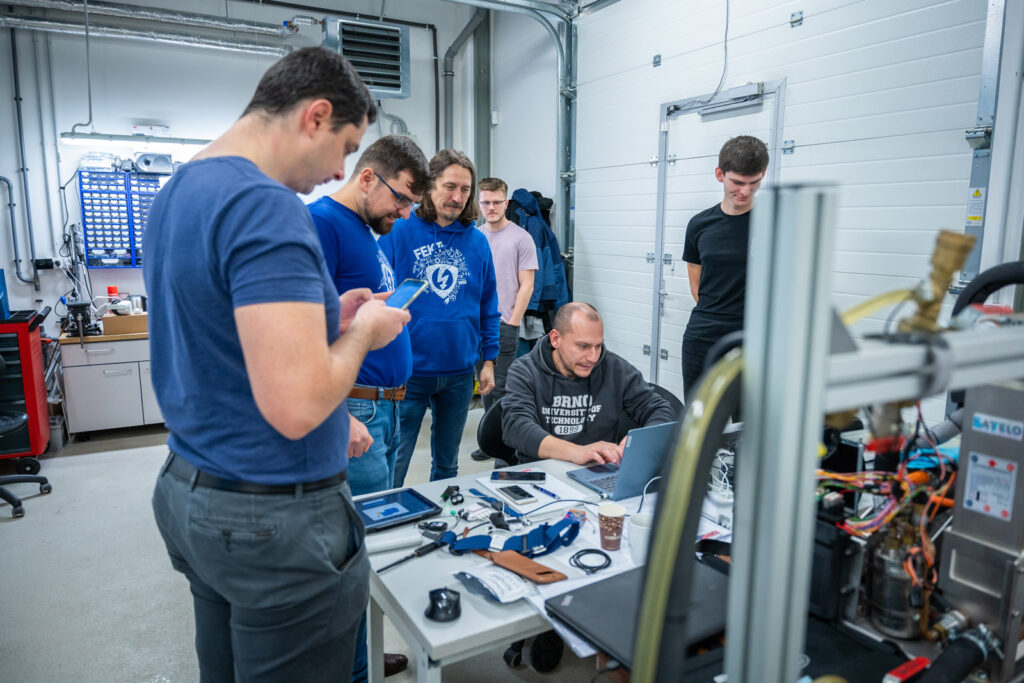

We would like to share with you some great news from our colleagues in Brno. At the beginning of December, a team of researchers from VUT led by Uptimai tested volunteers in the climate chamber at the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering. Major Ales Svoboda, ESA backup astronaut, also took part in the test.

Test persons will have two stays in the climate chamber. The first one under normal conditions at room temperature, the second one at an elevated temperature feeling reminiscent of a rather unpleasant tropical climate. In both cases, a battery of demanding neuropsychological tests, which were specifically designed for high-performance astronauts, are designed to increase the mental workload and thus the stress response of the test subject. In the second case, the aforementioned high temperature and humidity are then added as stressors.

Research leader Vratislav Šálený from the Faculty of Engineering explains the procedure:

“We are now seeing a colleague in the climate chamber. He’s just sitting quietly for ten minutes now, getting used to the environment. I’m about to bring him a tablet to test his cognitive functions.” This is not just any test, it is the same one used in NASA’s Twins Study to test the cognitive function of astronauts on the International Space Station. “The idea is to subject the test subject to a very intense cognitive load. Which is exactly right for us because the goal of our research is to measure stress. We also piloted the induction of cognitive load using virtual reality tools in collaboration with Deloitte,” Šálený adds.

While engineers from the Faculty of Mechanical Engineering create the necessary conditions in the climate chamber, the actual measurement of body functions is handled by biomedical engineering experts from the neighbouring Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Communication Technology (FEKT). “During the measurements, we monitor a single-lead ECG, and we monitor the respiratory rate using a sensor placed in the chest belt, on which we also have additional body temperature sensors. The subject also uses a metallyser measuring mask, thanks to which we obtain data on exhaled CO2, which is one of the important parameters for calculating the stress load,” says Jana Kolářová from the Institute of Biomedical Engineering. She adds that the course of the entire measurement was approved in advance by the ethics committee and all the subjects were briefed in detail about the entire course of the measurement before the start of the experiment.

foto: Václav Koníček

foto: Václav Koníček

One of the devices is operated by Dominik Bachratý, a student studying Sports Technology at the VUT. “In the second and third year we have to complete 480 hours of professional practice as part of a professionally oriented study programme. I was interested in the measurements of exercise physiology that are made at our Sports Activity Centre. I was trained and now I help with the measurements in the laboratory,” explains Bachratý, who got to do real research during his studies. During the test in the climate chamber, he is in charge of operating the aforementioned “mask”, which is actually a very sophisticated complex instrument for analysing gas exchange. “We are interested in oxygen consumption and CO2 production, or ventilation quotients, respiratory exchange ratio and heart rate,” he explains, while preparing the device for further measurements.

Stress is to some extent natural for humans and they can cope with it. “The human body is a closed system. The moment you are exposed to stressful conditions, your body immediately reacts and triggers mechanisms that try to keep your body in optimal conditions,” Kolářová explains. While all the previous test subjects are a sample of the standard young population, the latest test subject is Major Ales Svoboda. “In pilots or athletes – generally trained individuals – the body reacts to changes more quickly and does not allow the body to fluctuate at all as much as we see in an untrained person. For this reason we found Major Svoboda’s participation in the test very interesting. We have the opportunity to compare the measured physiological changes in a group of young untrained individuals with the pilot, for whom we expect a different course,” adds Kolářová.

foto: Václav Koníček

The combat pilot and, since last autumn, a member of ESA’s astronaut backup team, has all the ingredients to stand out from the other measurements. And first impressions after the test confirm that he is used to similar conditions. “The temperature was fine, I enjoyed the tests. So I guess I wasn’t stressed at all,” he says with a smile, adding that he often undergoes similar tests as a pilot. “We were talking at a conference recently about how stress – as long as it doesn’t exceed a certain limit – is actually useful. It’s the body’s compensation mechanism and preparation for a stressful situation. So being slightly stressed is basically good,” he assesses.

The data from the measurements will be processed by Uptimai, a Czech startup that deals with probabilistic modelling, both for industry and space research. The result of the development is to be a wearable device that can alert the user that his or her stress level is approaching a problematic threshold. The technology is also intended to use advanced algorithms and machine learning methods to measure stress markers in the human body to process physiological data. “The goal is to create a comprehensive real-time stress monitoring system that can be used in a range of fields: from healthcare workers, to firefighters, to civilian employees in high-stress situations,” explains researcher Šálený. If the research comes to a successful conclusion, this will be another example where people on the ground can benefit from what was originally space research.

There is no doubt that space research has benefits for everyday life as well. “I think it is not just a question of whether we will have our own Czech satellite or astronaut. Investment in space research is also reflected in business. That’s why we as a country should have a bit bigger goals, or we will miss the train, because countries like Poland and Hungary are doing much more than we are. In the meantime, we are at least trying to get back to where we were in the 1970s. We could do with more ambition,” concludes Svoboda.